All-Weather Stock Funds Do Exist

Unfortunately, almost nobody owns them.

Dodging the Bear

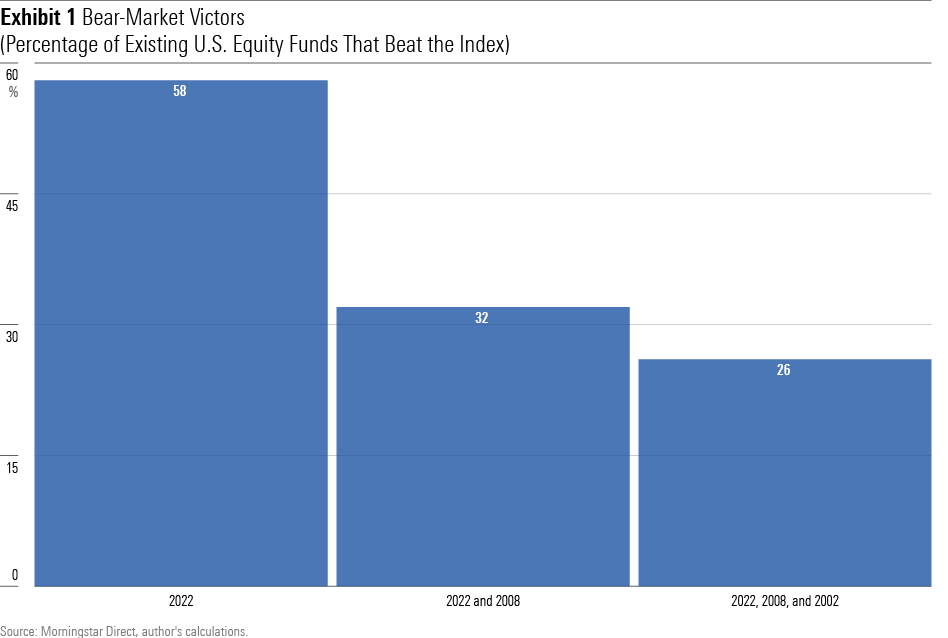

Before attempting to identify all-weather stock funds, it’s worth testing to see whether such things exist. To assess that proposition, I evaluated the returns of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds during the three bear-market years of 2022, 2008, and 2002. Eligible candidates were diversified U.S. equity funds that existed through that 21-year period, investing an average of at least 85% of their assets in stocks.

Of the 953 funds that possessed the requisite history, 550 lost less than the Morningstar US Market Index during 2022, for a bear-market success rate of 58%. Of course, because I defined “success” as any return higher than negative 19.43%, the term is very much relative. Nevertheless, among the group that was evaluated, more equity funds than not outdid the costless index.

Requiring the all-weather contenders to have also beaten the index in 2008 whittled the list to 305 funds, thereby creating a 32% success rate. Adding the additional hurdle of 2002 shrunk the group to 251 funds, for a 26% success rate.

That outcome suggests persistence. If fund performance had occurred randomly, then one would expect roughly 50% of funds to clear the initial barrier, 25% the first two hurdles, and 12.5% all three. (The percentages would be lowered by the drag of fund expenses but raised by their cash holdings. Overall, a wash.) As the actual totals were considerably higher, especially for the three-fund test, we can reasonably assume that some U.S. equity funds do tend to resist bear markets.

Riding the Bull?

Then again, managing downturns is only half the battle. Ultimately, what matters for equity investors are long-term gains. Conservatively positioned funds need not keep pace with equity rallies to justify their fees, but they must at least stay within sight of the pack, so that their overall results are competitive. It does shareholders no good if their funds are bear-market heroes but bull-market duds.

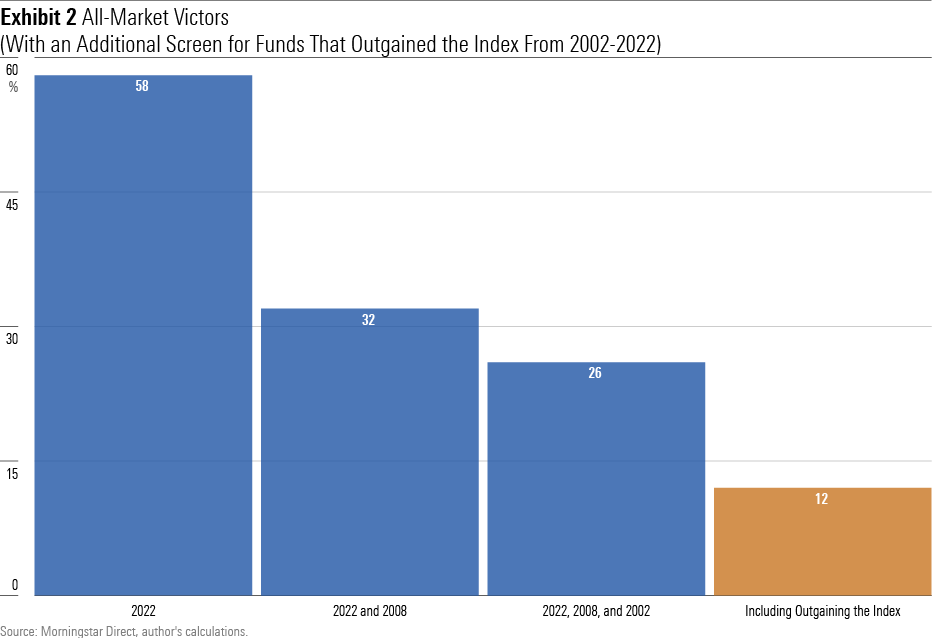

Thus, a full indicator of all-weather funds must include their overall performance. From 2002 through 2021, the Morningstar US Market Index gained an annualized 8.17% (which, not entirely coincidentally, was also the figure for Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSMX). Among the 251 bear-market survivors, 112 funds—representing 12% of the original population—surpassed that amount.

That struck me as a high percentage. Indeed, I would wager that many veteran fund observers, familiar with the arithmetic of active management, might have guessed that only 12% of funds in total outgained the stock market over the past 21 years, never mind doing so while also outdoing the indexes during each of the three worst bear markets. There appear to be many all-weather candidates.

The surfeit, however, is a mirage. As previously stated, losing 19.42% when an index sheds 19.43% is “all-weather” in name only. Although stock-fund investors should not expect to turn a profit during market retreats, they can justifiably hope for meaningfully lower losses. Seventy percent seems like a reasonable, albeit arbitrary, figure. I will therefore define all-weather U.S. equity funds as those funds that have outgained the overall stock market over the long haul while also experiencing less than 70% of the stock market’s decline in 2002, 2008, and 2022.

The All-Weather Winners

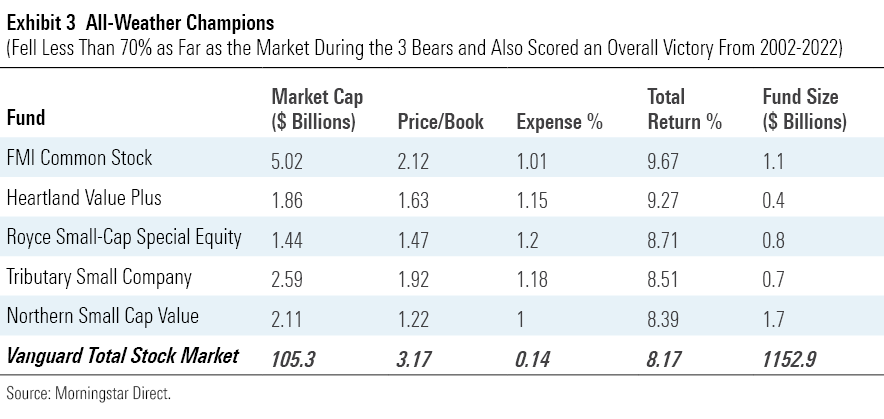

Adding that constraint narrows the field to just five. Now came the surprise. I had expected the finalists to invest in blue-chip stocks—old-line companies that trade at modest prices because their businesses are mature. However, their operations are dependable and consistently profitable. Representative industries include consumer staples and healthcare providers. Stocks from those sectors typically end up in dividend-paying funds, such as Vanguard Dividend Growth VDIGX.

But Vanguard Dividend Growth did not make the all-weather club. Nor did any other fund that favors either high dividends or blue chips. Quite the contrary. The five champions each invest primarily in companies that pay modest or no dividends and that lie outside the S&P 500. What’s more, those firms, while established, do not boast high scores for Morningstar’s measure of business safety (economic moats) nor its measure of financial health. Consequently, their stocks are cheap.

As the table shows, the all-weather winners stand out from the mainstream. Across the board, they differ from the world’s largest mutual fund, Vanguard Total Stock Market Index. Each of the five all-weather funds is sponsored by a niche organization. The funds have relatively few shareholders, and their performances are driven by small to midsized companies that sell at low price multiples. Predictably, their expense ratios also sharply exceed that of the index fund.

This result conforms with the predictions of academic finance, which for 40 years has claimed that both small companies and value stocks offer a return “premium.” In recent years, though, researchers have noted the seeming disappearance of the size and value effects, leading to articles asking “Is Small-Cap Value Dead?”, or “Do Value Stocks Really Outperform Growth Stocks Over The Long Run?” The all-weather winners, to their credit, bucked the trend.

Summary

There’s much to like about dividend-growth funds. On average, U.S. equity funds that have the word “dividend” in their names have matched the stock market’s 21-year returns before expenses while trailing only modestly after their costs are considered. What’s more, their risk, as measured both by standard deviation and bear-market results, has been slightly lower. Those funds have been fine.

However, the most successful all-weather funds walk where others have feared to tread. Their rivals’ reluctance is understandable. Small-value funds can languish for long bull-market stretches, as during the late 1990s and then again two decades later. Those times are intensely frustrating. (Perhaps even worse for investors than suffering outright losses is watching while others score fat profits.) Such lulls, along with unfavorable publicity, have limited the amount of assets in small-value funds—especially, as we have seen, among the all-weather winners.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)